.

I Introduction

.

Whatever is your role in the aviation industry ( be it a private or commercial pilot, an air traffic controller, an engineer, … ), this article is intended to provide you with an enhanced understanding of aircraft automation (understood here as automatic flight guidance), , how pilots interface with automated systems and how the optimum use of automation contributes to the overall management of the aircraft flight path. Although different aircraft generations or models may provide different levels of systems integration and automation, the guiding principles of automation remain essentially the same. High levels of automation provide flight crews with an increasing number of options and strategies to choose for the task to be accomplished (e.g., to comply with ATC requirements, …). The purpose of this article is to recall and demystify some of the fundamental aspects involved in using and supervising automation; it is also intended to constitute a brief “automation refresher” for pilots. Strict adherence to the following guiding principles and golden rules of operation enhances flight crew’s situational awareness (guidance awareness) and prevents so called “automation surprises”.

.

II Understanding Automation

.

The design objective of the automatic flight system (AFS) is to provide assistance to the crew throughout the flight (within the normal flight envelope), by :

- Relieving the pilot-flying (PF) from routine handling tasks and thus allowing time and resources to enhance his/her situational awareness or for problem solving tasks; or,

- Providing the PF with attitude and flight path guidance through the flight director (FD), for hand flying.

Basically, the AFS provides guidance to capture and maintain the selected targets and the defined flight path, in accordance with the modes engaged and the targets set by the flight crew on the flight guidance control panel (usually referred to as the flight control unit – FCU – or mode control panel – MCP) or on the flight management system control and display unit (FMS CDU). Understanding any automated system, but particularly the AFS and FMS, requires being able to answer the following questions:

- How is the system designed ?

- How does the system interface and communicate with the pilot ?

- How to operate the system in normal and abnormal situations ?

The following aspects should be fully understood for an optimum use of automatic flight guidance:

- Integration of autopilot / flight director (AP/FD) and autothrottles / autothrust (A/THR) modes (i.e., pairing of modes);

- Modes transition sequences; and,

- Pilot-system interfaces for:

– Pilot-to-system communication (i.e., for selecting guidance targets and arming / engaging AP/FD – A/THR modes); and,

– System-to-pilot feedback (i.e., for checking the status of modes armed or engaged and the correctness of active guidance targets).

.

III AP – A/THR Integration

.

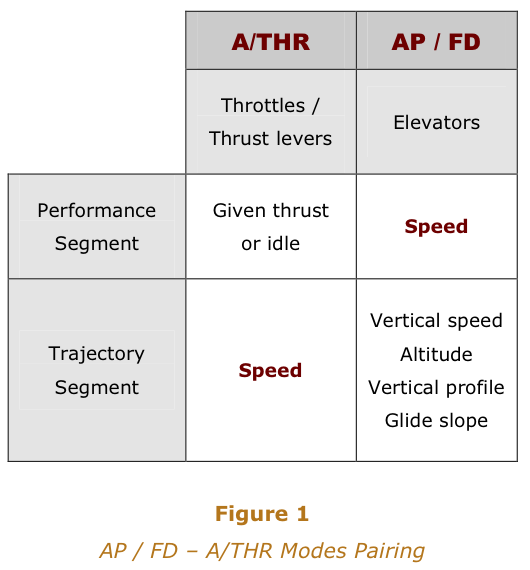

Integrated AP – A/THR systems feature an association (pairing) of AP pitch modes (elevator control) and A/THR modes (throttle levers / thrust control). An integrated AP – A/THR operates in the exact same way as a human pilot :

- Elevator is used to control pitch attitude, airspeed, vertical speed, altitude, flight-path-angle, vertical navigation profile or to capture and track a glide slope beam;

- Throttle / thrust levers are used to maintain a given thrust or a given airspeed.

Indeed, throughout the flight, the pilot’s objective is to fly:

- Performance segments at constant thrust or at idle (e.g., takeoff, climb or descent);

- or, Trajectory segments at constant speed (e.g., cruise or approach). Depending on the task to be accomplished, maintaining the airspeed is assigned – automatically – either to the AP (elevators) or to the A/THR (throttles levers / thrust control), as shown in Figure 1. .

.

IV Flight Crew / System Interface

.

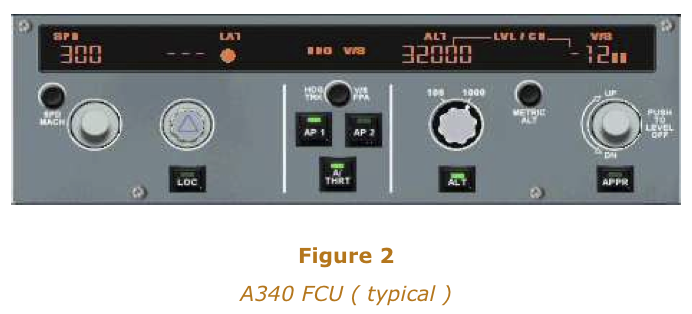

The FCU constitutes the main interface between the pilot and the autoflight system for short-term guidance (i.e., for immediate guidance).

The FMS CDU constitutes the main interface between the pilot and the autoflight system for long-term guidance (i.e., for the current and subsequent flight phases).

Figure 3

A 340 FMS CDU (Typical)

When performing an action on the FCU or FMS CDU to give a command to the AFS, the pilot has an expectation of the aircraft reaction and, therefore, must have in mind the following questions:

- What do I want the aircraft to fly now ?

- What do I want the aircraft to fly next ?

This implies the awareness and understanding of the following aspects :

- Which mode did I engage and which target did I set for the aircraft to fly now ?

- Is the aircraft following the intended vertical and lateral flight path and targets ?

- Which mode did I arm and which target did I preset for the aircraft to fly next ?

To enable answering the above questions, the roles of the following controls and displays must be understood:

- FCU (mode selection-keys, target-setting knobs and display windows);

- FMS CDU (keyboard, line-select keys, display pages and messages);

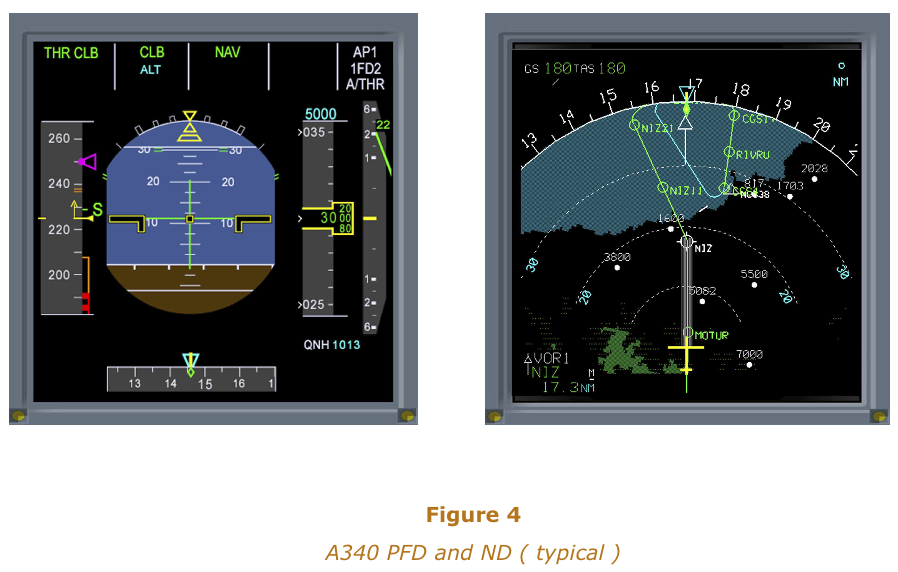

- FMA (Flight Mode Annunciator) on PFD; and,

- PFD and ND (Navigation Display) displays and scales (i.e., for cross-checking active guidance targets).

The effective monitoring of these controls and displays promotes and increases the flight crew awareness of the available / active guidance for flight path and speed control, this includes :

- Modes (i.e., AP/FD modes being engaged or armed); and,

- Targets (i.e., altitude, speed or vertical speed or vertical navigation, heading or lateral navigation).

The safe use of AP, A/THR and FMS requires adopting the following three-step approach:

• Anticipate:

− Understand system operation and the results of any action, − Be aware of the modes being engaged or armed; and, − Understand mode transitions or reversions,

• Execute:

− Perform action(s) on FCU or on FMS CDU,

• Confirm:

− Crosscheck and announce the effective arming or engagement of modes and the correctness of active guidance targets (on FMA, PFD and/or ND scales and/or FMS CDU),

− Observe the aircraft response and resulting trajectory. V Operations Golden Rules

.

V Operations Golden Rules

.

The following golden rules of operation and supervision of automation enable the flight crew to stay ahead of the aircraft and be prepared for possible contingencies.

Taking advantage of automation to reduce workload

The use of automated systems reduces workload and significantly improves the flight crew time and resources for responding to:

- Any unanticipated change (e.g., ATC instruction, weather conditions, …);

- or, Any abnormal or emergency condition.

During line operations, AP and A/THR should be engaged, especially in marginal weather conditions or when operating into an unfamiliar airport.

Using AP and A/THR enables flight crew to pay more attention to ATC communications and to other aircraft, particularly in congested terminal areas and at high-density airports.

When operating in fair environmental conditions and at low-density airports, flight crew can elect to fly the departure or arrival manually to maintain manual flying skills.

Conditions permitting, AP and A/THR should be used to fly unplanned maneuvers – such as a missed-approach – to reduce workload.

Using the correct level of automation for the task

On highly automated and integrated aircraft, several levels of automation are available to perform a given task.

The correct level of automation depends on :

- The task to be performed:

− short-term task (i.e., tactical choice, short and head-up action(s) on FCU, immediate aircraft response); or,

− long-term task (i.e., strategic choice, longer and head-down action(s) on FMS CDU, longer term aircraft response);

- The flight phase:

− departure; − enroute climb / cruise / descent; − terminal area; or, − approach; and,

- The time available:

− normal selection or entry; or, − last-minute change.

The PF always retain the authority and capability to select the most appropriate level of automation and guidance for the task, this includes:

- Adopting a more direct level of automation by reverting from FMS-managed guidance to non-FMS guidance (i.e., using the FCU for modes selections and targets entries);

- Selecting a more appropriate lateral or vertical mode; or,

- Reverting to hand flying (with or without FD guidance, with or without A/THR), for direct control of aircraft vertical trajectory, lateral trajectory and thrust.

The correct level of automation often is the one the pilot feels comfortable with for the task or for the prevailing conditions, depending on his/her own knowledge and experience of the aircraft and systems.

Pilots with high experience on type tend to use automation in a simpler way than recently- qualified pilots who tend to explore higher levels of automation … with the resulting risk of error or loss of mode awareness.

Being aware of available guidance at all times.

The FCU and the FMS CDU are the prime interfaces for the flight crew to communicate with the aircraft systems (i.e., to set targets and arm or engage modes).

The PFD and ND are the prime interfaces for the aircraft to communicate with the flight crew, to confirm that the aircraft systems have correctly accepted the mode selections and the target entries:

- PFD (FMA, speed scale and altitude scale): − guidance modes, speed and altitude targets;

- ND ( heading / track scale or FMS flight plan): − lateral guidance.

Any action on the FCU or on the FMS CDU (keyboard and line-select keys) should be confirmed by cross-checking the corresponding annunciation or target on the PFD and/or ND, and on the FMS CDU display.

The use and operation of the AFS must be monitored / supervised at all times by:

- Announcing the status of AP/FD modes and A/THR mode on the FMA (i.e., mode arming or engagement, mode changeovers);

- Announcing the result of any change of guidance target on the related PFD and/or ND scales; and,

- Supervising the resulting AP/FD guidance and A/THR operation on the PFD and ND (i.e., pitch attitude and bank angle, speed and speed trend, altitude, vertical speed, heading or track, …).

At all times, the PF and PNF / PM (pilot-not-flying / pilot-monitoring) should be aware of the status of the active guidance targets, of the guidance modes being armed or engaged and of any mode changeover throughout mode transitions or reversion.

Being ready and alert to take over, if required

Supervising automation is simply “ Flying with your eyes “, observing cockpit displays and indications to ensure that the aircraft response matches your mode selections and guidance target entries, and that the aircraft attitude, speed and trajectory match your expectations.

If any doubt exists regarding the aircraft flight path or speed control, no attempt at reprogramming the automated systems should be made (unless an obvious entry error is detected).

A lower level of automation or hand-flying with reference to navaids raw data should be used until time and conditions permit reprogramming the AP/FD or FMS.

If AP or A/THR operation needs to be overridden following a malfunction, such as a runaway or hardover, the affected system must be immediately disconnected by pressing the associated instinctive disconnect push button.

Outside emergency situations, AP and A/THR must not be overridden manually.

.

VI Closing Remarks

.

Ideally, automation should match the pilot’s mental model for flying the aircraft from gate to gate, it therefore should be intuitive.

However, automation requires some measure of ” pilot’s appropriation “ through training and line practice.

As an aviation professional, you had already an idea of the level of automation which a modern aircraft type provides but you probably did not know precisely the extent to which it is being used and how operational constraints may affect this use ; perhaps this article has opened your eyes to the scope and pilot use of automation in the flight deck and helped you appreciate both its potential but also its pitfalls for pilots.

By Michel TREMAUD ( retired, Airbus / Aerotour / Air Martinique / Bureau Veritas )

..